Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Many investors are preoccupied with returns, and understandably so, however returns are simply half of the picture. The development of Probability Theory by Pascal and Fermat in 1654 opened the way for measuring and quantifying risk and the establishment of the field of financial economics and econometrics that gives form to so much of investment theory today. Risk management is a critical tool in a successful investment experience. The work that these two French Mathematicians did, laid the groundwork for understanding not only valuations but the potential reward that should be the reasonable prerequisite to taking on risks. There can be no reward without risk so it was best to understand what risks were lurking even if they weren’t immediately obvious. This has enabled investors to better deal with uncertainty.

Nearly a century later, investment management was revolutionised by Harry Markowitz with his 1952 paper simply titled “Portfolio Selection.” It fired the shot that reverberated around the world and set the parameters that form the basis of wealth management to this day. His paper was innovative in so far as it dealt with the entire portfolio as an entity rather than individual holdings. He was able to demonstrate that it was the interrelationships between the parts that were more important than the individual parts. Up until the time of his paper all research and analysis was focused on the holdings considered individually. He was a mathematician with no knowledge or interest in the share market prior to preparing for his doctoral dissertation when he had a chance meeting with a stock broker who inspired him to investigate the problems investors face in the market. He was interested in the broader concept of how people can make the best decisions when dealing with the trade-offs in life. He was inspired by the notion that investors should be interested in risk as well as return while reading John Burr Williams book, “The Theory of Investment Value.” The first line of the book was: “No buyer considers all securities equally attractive at their present market prices… on the contrary, he seeks ‘the best at the price.’”[1] Markowitz realised that the implications of this were that taking this to its logical conclusion, the investor would buy the one stock that was most attractive. The reason this didn’t happen in the real world was a belief that you don’t bet all you have on the one roll of the dice, so therefore investors must be interested in risk as well as return.

Markowitz set out to use the notion of risk to construct portfolios for investors who “consider expected return a desirable thing and variance of return an undesirable thing” He uses variance as a proxy for risk. For the first time risk (variance) was something that could be measured and also reduced by diversification. “Diversification, is both observed and sensible; a rule of behaviour which does not imply the superiority of diversification must be rejected both as a hypothesis and as a maxim”[2], was the way that Markowitz described it. It was the mathematics of diversification that made this so attractive. “While the return on a diversified portfolio will be equal to the average of the rates of return on its individual holdings, its volatility will be less than the average volatility of its individual holdings. This means that diversification is a kind of free lunch at which you can combine a group of risky securities with high expected returns into a relatively low risk portfolio, so long as you minimise the covariances, or correlations, among the returns of the individual securities.[3]

Markowitz received the Nobel Prize for economics for his 1952 paper, which is regarded as the beginning of Modern Portfolio Theory. The concept that you can reduce the overall volatility of your portfolio by diversifying your investments among a group of non-correlating asset classes was a major breakthrough. When one asset class such as shares was falling in value, your diversification into bonds and real estate would help hold the value of your portfolio relatively steady.

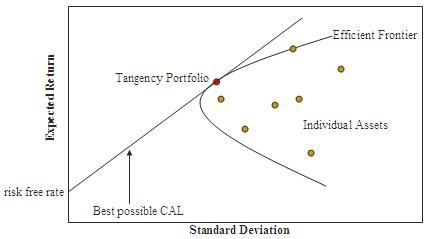

The Markowitz model is a single period model where the portfolio is formed at the beginning of the period. He uses volatility (or standard deviation) as a measure of risk. The investor’s objective is to maximise the portfolio’s expected return, subject to an acceptable level of risk or to take the least amount of risk to achieve a specific return. This relationship can be charted on an efficient frontier that graphs the standard deviation of a portfolio against its return.

“As securities are added to a portfolio, the expected return and standard deviation change in very specific ways, based on the way in which the added securities co-vary with the other securities in the portfolio. The best that an investor can do (i.e., the furthest northwest a portfolio can be) is bounded by a curve that is the upper half of the hyperbola, as shown in Figure 1. This curve is known as the efficient frontier. According to the Markowitz model, rational investors select portfolios along this curve, according to their tolerance for risk. An investor who can live with a lot of risk might choose a portfolio along the north eastern side of the curve, while a more risk-averse investor would be more likely to choose portfolio closer to the tangency portfolio. One of the major insights of the Markowitz model is that a security’s expected return, coupled with how it co-varies with other securities, that determines how it is added to investor portfolios.”[4]

Imagine a dance floor with couples dancing to the rhythm of the music. Each couple represents a pair of assets in a portfolio, and their movements symbolize changes in the value of the assets. Markowitz’s covariance theory can be thought of as a measure of how closely the dance partners move together in response to the music (i.e, the market/economic factors). If the couples are dancing to a waltz, you would desire that they move in a synchronized manner – when one partner takes a step forward, the other moves forward in the same direction, maintaining their position relative to one another. Now lets imagine that the music changes to a tango. In this instance, the dance becomes more intricate with instances where one partner moves forward and the other moves backwards or to the side. In this case, the dance partners are less synchronized and it is often desirable for them to move in opposite directions at times. Now imagine a rave, with each dancer incorporating their own movements, dipping, and weaving entirely independent of other dancers.

Whether we desire to construct a portfolio with holdings that are positively correlated (waltzing), negatively correlated (tangoing) or entirely uncorrelated (raving) will depend on the objective of individual investors. Like choreographers coordinating a dance, investors need to be clear on what their specific intentions are. Harry Markowitz took the chaos of markets and developed models that simplified and allowed investors to dance amongst the noise. By his legacy we understand that no two investors are the same, investors are liberated from being distracted by others and can begin focusing instead on moving within their own comfort zones and taking steps necessary to dance their own dance.

[1] Williams, John Burr, 1938 “The Theory of Investment Value.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press p1

[2] Markovitz, Harry M. 1952. “Portfolio Selection.” Journal of Finance, Vol VII, No. 1 (March), pp77-91

[3] Bernstein, Peter L. 1996. “Against the Gods, the remarkable story of risk.” John Wiley & Sons p253

[4] Davis, James L. 2001.”Explaining Stock Returns: A Literature Survey.” Dimensional Fund Advisors Inc p2